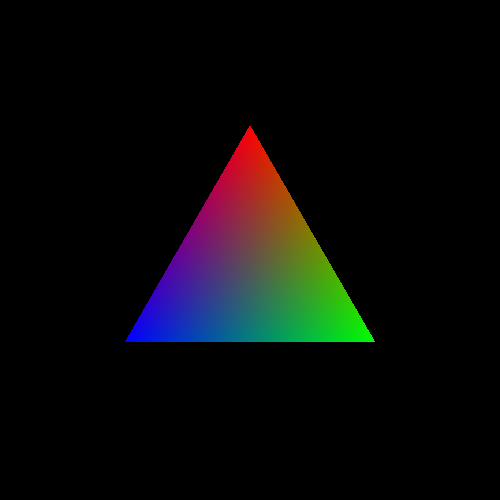

Using the fragment position in a fragment shader is quite useful, but it is far from

the best tool for controlling the color of triangles. A much more useful tool is to give

each vertex a color explicitly. The Vertex Colors

tutorial implements this; the main file for this tutorial is

VertexColors.cpp.

We want to affect the data being passed through the system. The sequence of events we want to happen is as follows.

-

For every position that we pass to a vertex shader, we want to pass a corresponding color value.

-

For every output position in the vertex shader, we also want to output a color value that is the same as the input color value the vertex shader received.

-

In the fragment shader, we want to receive an input color from the vertex shader and use that as the output color of that fragment.

You most likely have some serious questions about that sequence of events, notably about how steps 2 and 3 could possibly work. We'll get to that. We will follow the revised flow of data through the OpenGL pipeline.

In order to accomplish the first step, we need to change our vertex array data. That data now looks like this:

Example 2.2. New Vertex Array Data

const float vertexData[] = {

0.0f, 0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f,

0.5f, -0.366f, 0.0f, 1.0f,

-0.5f, -0.366f, 0.0f, 1.0f,

1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f,

0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f,

0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f,

};

First, we need to understand what arrays of data look like at the lowest level. A single byte is the smallest addressible data in C/C++. A byte represents 8 bits (a bit can be 0 or 1), and it is a number on the range [0, 255]. A value of type float requires 4 bytes worth of storage. Any float value is stored in 4 consecutive bytes of memory.

A sequence of 4 floats, in GLSL parlance a vec4, is exactly that: a

sequence of four floating-point values. Therefore, a vec4 takes

up 16 bytes, 4 floats times the size of a float.

The vertexData variable is one large array of floats. The way

we want to use it however is as two arrays. Each 4 floats is a single

vec4, and the first three vec4s represents the

positions. The next 3 are the colors for the corresponding vertices.

In memory, the vertexData array looks like this:

The top two show the layout of the basic data types, and each box is a byte. The bottom diagram shows the layout of the entire array, and each box is a float. The left half of the box represents the positions and the right half represents the colors.

The first 3 sets of values are the three positions of the triangle, and the next 3

sets of values are the three colors at these vertices. What we really have is two

arrays that just happen to be adjacent to one another in memory. One starts at the

memory address &vertexData[0], and the other starts at the

memory address &vertexData[12]

As with all vertex data, this is put into a buffer object. We have seen this code before:

Example 2.3. Buffer Object Initialization

void InitializeVertexBuffer()

{

glGenBuffers(1, &vertexBufferObject);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, vertexBufferObject);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeof(vertexData), vertexData, GL_STATIC_DRAW);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0);

}

The code has not changed, because the size of the array is computed by the

compiler with the sizeof directive. Since we added a few elements

to the buffer, the computed size naturally grows bigger.

Also, you may notice that the positions are different from prior tutorials. The original triangle, and the one that was used in the Fragment Position code, was a right triangle (one of the angles of the triangle is 90 degrees) that was isosceles (two of its three sides are the same length). This new triangle is an equilateral triangle (all three sides are the same length) centered at the origin.

Recall from above that we are sending two pieces of data per-vertex: a position and a color. We have two arrays, one for each piece of data. They may happen to be adjacent to one another in memory, but this changes nothing; there are two arrays of data. We need to tell OpenGL how to get each of these pieces of data.

This is done as follows:

Example 2.4. Rendering the Scene

void display()

{

glClearColor(0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f);

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

glUseProgram(theProgram);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, vertexBufferObject);

glEnableVertexAttribArray(0);

glEnableVertexAttribArray(1);

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, 0, 0);

glVertexAttribPointer(1, 4, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, 0, (void*)48);

glDrawArrays(GL_TRIANGLES, 0, 3);

glDisableVertexAttribArray(0);

glDisableVertexAttribArray(1);

glUseProgram(0);

glutSwapBuffers();

glutPostRedisplay();

}

Since we have two pieces of data, we have two vertex attributes. For each

attribute, we must call glEnableVertexAttribArray to enable

that particular attribute. The first parameter is the attribute location set by the

layout(location) field for that attribute in the vertex

shader.

Then, we call glVertexAttribPointer for each of the attribute

arrays we want to use. The only difference in the two calls are which attribute

location to send the data to and the last parameter. The last parameter is the byte

offset into the buffer of where the data for this attribute starts. This offset, in

this case, is 4 (the size of a float) * 4 (the number of

floats in a vec4) * 3 (the number of

vec4's in the position data).

Note

If you're wondering why it is (void*)48 and not just

48, that is because of some legacy API cruft. The reason

why the function name is glVertexAttrib“Pointer” is because the

last parameter is technically a pointer to client memory. Or at least, it could

be in the past. So we must explicitly cast the integer value 48 to a pointer

type.

After this, we use glDrawArrays to render, then disable the

arrays with glDisableVertexAttribArray.

In the last tutorial, we skimmed over the details of what exactly

glDrawArrays does. Let us take a closer look

now.

The various attribute array functions set up arrays for OpenGL to read from when rendering. In our case here, we have two arrays. Each array has a buffer object and an offset into that buffer where the array begins, but the arrays do not have an explicit size. If we look at everything as C++ pseudo-code, what we have is this:

Example 2.5. Vertex Arrays

GLbyte *bufferObject = (void*){0.0f, 0.5f, 0.0f, 1.0f, 0.5f, -0.366f, ...};

float *positionAttribArray[4] = (float *[4])(&(bufferObject + 0));

float *colorAttribArray[4] = (float *[4])(&(bufferObject + 48));

Each element of the positionAttribArray contains 4

components, the size of our input to the vertex shader (vec4). This is the case

because the second parameter of glVertexAttribPointer is 4.

Each component is a floating-point number; similarly because the third parameter

is GL_FLOAT. The array takes its data from

bufferObject because this was the buffer object that was

bound at the time that glVertexAttribPointer was called.

And the offset from the beginning of the buffer object is 0 because that is the

last parameter of glVertexAttribPointer.

The same goes for colorAttribArray, except for the offset

value, which is 48 bytes.

Using the above pseudo-code representation of the vertex array data,

glDrawArrays would be implemented as follows:

Example 2.6. Draw Arrays Implementation

void glDrawArrays(GLenum type, GLint start, GLint count)

{

for(GLint element = start; element < start + count; element++)

{

VertexShader(positionAttribArray[element], colorAttribArray[element]);

}

}

This means that the vertex shader will be executed count

times, and it will be given data beginning with the start-th

element and continuing for count elements. So the first time

the vertex shader gets run, it takes the position attribute from

bufferObject[0 + (0 * 4 * sizeof(float))] and the color

attribute from bufferObject[48 + (0 * 4 * sizeof(float))].

The second time pulls the position from bufferObject[0 + (1 * 4 *

sizeof(float))] and color from bufferObject[48 + (1 * 4 *

sizeof(float))]. And so on.

The data flow from the buffer object to the vertex shaders looks like this now:

As before, every 3 vertices processed are transformed into a triangle.

Our new vertex shader looks like this:

Example 2.7. Multi-input Vertex Shader

#version 330

layout (location = 0) in vec4 position;

layout (location = 1) in vec4 color;

smooth out vec4 theColor;

void main()

{

gl_Position = position;

theColor = color;

}

There are three new lines here. Let us take them one at a time.

The declaration of the global color defines a new input for the

vertex shader. So this shader, in addition to taking an input named

position also takes a second input named

color. As with the position input, this

tutorial assigns each attribute to an attribute index. position

is assigned the attribute index 0, while color is assigned

1.

That much only gets the data into the vertex shader. We want to pass this data out

of the vertex shader. To do this, we must define an output

variable. This is done using the out keyword. In

this case, the output variable is called theColor and is of type

vec4.

The smooth keyword is an interpolation

qualifier. We will see what this means a bit later.

Of course, this simply defines the output variable. In main,

we actually write to it, assigning to it the value of color that

was given as a vertex attribute. This being shader code, we could have used some

other heuristic or arbitrary algorithm to compute the color. But for the purpose of

this tutorial, it is simply passing the value of an attribute passed to the vertex

shader.

Technically, the built-in variable gl_Position is defined as

out vec4 gl_Position. So it is an output variable as well. It

is a special output because this value is directly used by the system, rather than

used only by shaders. User-defined outputs, like theColor above,

have no intrinsic meaning to the system. They only have an effect in so far as other

shader stages use them, as we will see next.

The new fragment shader looks like this:

Example 2.8. Fragment Shader with Input

#version 330

smooth in vec4 theColor;

out vec4 outputColor;

void main()

{

outputColor = theColor;

}

This fragment shader defines an input variable. It is no coincidence that this

input variable is named and typed the same as the output variable from the vertex

shader. We are trying to feed information from the vertex shader to the fragment

shader. To do this, OpenGL requires that the output from the previous stage have the

same name and type as the input to the next stage. It also must use the same

interpolation qualifier; if the vertex shader used smooth, the

fragment shader must do the same.

This is a good part of the reason why OpenGL requires vertex and fragment shaders to be linked together; if the names, types, or interpolation qualifiers do not match, then OpenGL will raise an error when the program is linked.

So the fragment shader receives the value output from the vertex shader. The shader simply takes this value and copies it to the output. Thus, the color of each fragment will simply be whatever the vertex shader passed along.

Now we come to the elephant in the room, so to speak. There is a basic communication problem.

See, our vertex shader is run only 3 times. This execution produces 3 output

positions (gl_Position) and 3 output colors

(theColor). The 3 positions are used to construct and

rasterize a triangle, producing a number of fragments.

The fragment shader is not run 3 times. It is run once for every fragment produced by the rasterizer for this triangle. The number of fragments produced by a triangle depends on the viewing resolution and how much area of the screen the triangle covers. An equilateral triangle the length of who's sides are 1 has an area of ~0.433. The total screen area (on the range [-1, 1] in X and Y) is 4, so our triangle covers approximately one-tenth of the screen. The window's natural resolution is 500x500 pixels. 500*500 is 250,000 pixels; one-tenth of this is 25,000. So our fragment shader gets executed about 25,000 times.

There's a slight disparity here. If the vertex shader is directly communicating with the fragment shader, and the vertex shader is outputting only 3 total color values, where do the other 24,997 values come from?

The answer is fragment interpolation.

By using the interpolation qualifier smooth when defining the

vertex output and fragment input, we are telling OpenGL to do something special with

this value. Instead of each fragment receiving one value from a single vertex, what

each fragment gets is a blend between the three output values

over the surface of the triangle. The closer the fragment is to one vertex, the more

that vertex's output contributes to the value that the fragment program

receives.

Because such interpolation is by far the most common mode for communicating

between the vertex shader and the fragment shader, if you do not provide an

interpolation keyword, smooth will be used by default. There are

two other alternatives: noperspective and

flat.

If you were to modify the tutorial and change smooth to

noperspective, you would see no change. That does not mean a

change did not happen; our example is just too simple for there to actually be a

change. The difference between smooth and

noperspective is somewhat subtle, and only matters once we

start using more concrete examples. We will discuss this difference later.

The flat interpolation actually turns interpolation off. It

essentially says that, rather than interpolating between three values, each fragment

of the triangle will simply get the first of the three vertex shader output

variables. The fragment shader gets a flat value across the surface of the triangle,

hence the term “flat.”

Each rasterized triangle has its own set of 3 outputs that are interpolated to compute the value for the fragments created by that triangle. So if you render 2 triangles, the interpolated values from one triangle do not directly affect the interpolated values from another triangle. Thus, each triangle can be taken independently from the rest.

It is possible, and highly desirable in many cases, to build multiple triangles from shared vertices and vertex data. But we will discuss this at a later time.